3076.

One thing that gets tedious pretty quick these days is the insistence of people on some kind of oracle.

The future, by definition, hasn't happened yet; it's unknowable. It's guessable. You can predict things, but there's always the chance that you'll be wrong, no matter how sure the thing, unless some sort of fix can be put it. But people will dream, so people will nominate oracles.

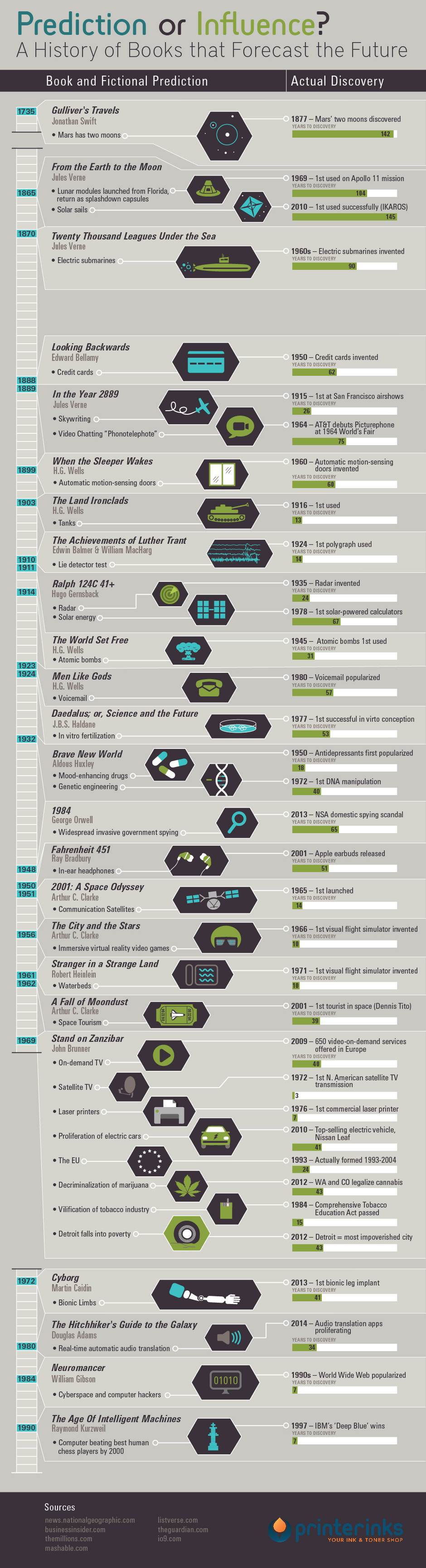

Modern days' favorite oracle is the well-envisioned science fiction story. SF, as a genre, seems to have had a contentious time with the idea that it is a predictor; at times, shunning the idea, at others, wholly embracing it. I have my own thoughts on the subject, but first, check this graphic out. The graphic was produced pretty much as blogbait by a printer ink purveyor (link after the graphic) but I found it carefully done, attractive, and quite enlightening. Please view, then join me again at the bottom.

Whew … that was a long one. Was worried you'd lose your way, but it's good to see you.

Okay. What have we got? Three columns, essentially: on the left, a timeline, with what the graphic artist considered notable books called out in the year of publication. In the middle, the noteworthy 'predictions' that the stories made, and on the right, a bar graph that's designed to quantify how apt the vision was by the number of years after publication that the envisioned development occurred. More green, the longer we had to wait.

One thing that comes right out, at me anyway, is the earlier works had much, much longer to wait before what they foresaw came into being. The laser visionary works gave much shorter lead times. This tells me something about technology and the willingness of the writers to go out on a limb. Writers today have so much instant information to work with, thanks to the Internet, the 24-hour news cycle … time was, we had to go out and get our information. These days, it gets pushed at us so fast that those basements we used to blog out of in the last decade are being used to hide from the onslaught in this.

More, so much newness is feeding back into the system so fast that it's influencing things a a much more pitched rate than ever before.

See, that's the difference I have with the 'SF as predictor' trope. SF doesn't predict anything. We see things we recognize in society and evolve to meet us. SF has never predicted anything, it's really just given us our number, gauged our character, and the most apt SF writers have taken these traits and played with them as a happy child with Legos does, putting them together into different combinations with situations and then seeing how they react. Are they stable … or do they fall apart?

Since SF so quickly enters the pop culture these days, it goes from entertainment to zeitgeist in record time. We evolve the direction we think it shows us because it's really not telling us anything we don't know about ourselves; we look into SF and see ourselves reflected back. SF only exists in the future because that's the place we're all going anyway.

So, I don't see SF as some sort of oracle; sure, Star Trek 'predicted' things like the iPad and the smart phone, but did it? We've always liked portable, flashy toys, and instantaneous communication and entertainment via personal devices didn't start with Star Trek. It just picked up a well-played ball, dressed it up in chrome and flippy cover, and ran with it with inimitable style. That's not to say that Trek didn't do it smashingly well … it did. I just thing that Trek gets maybe a little too much credit for envisioning our personal technological future. Dick Tracy gave us the 2-way wrist radio, after all.

Rather than predicting anything, SF does a sort of odd dance with the present, whispering into our ear what things might look like, and also asking us to think about them and what they do to us. Of course, we only half listen to that. But it's there, if we pay attention.

Maybe, like the crows we frequently make fun of, we get too obsessed with the bright shinies.

The future, by definition, hasn't happened yet; it's unknowable. It's guessable. You can predict things, but there's always the chance that you'll be wrong, no matter how sure the thing, unless some sort of fix can be put it. But people will dream, so people will nominate oracles.

Modern days' favorite oracle is the well-envisioned science fiction story. SF, as a genre, seems to have had a contentious time with the idea that it is a predictor; at times, shunning the idea, at others, wholly embracing it. I have my own thoughts on the subject, but first, check this graphic out. The graphic was produced pretty much as blogbait by a printer ink purveyor (link after the graphic) but I found it carefully done, attractive, and quite enlightening. Please view, then join me again at the bottom.

|

Infographic brought to you by PrinterInks

|

Okay. What have we got? Three columns, essentially: on the left, a timeline, with what the graphic artist considered notable books called out in the year of publication. In the middle, the noteworthy 'predictions' that the stories made, and on the right, a bar graph that's designed to quantify how apt the vision was by the number of years after publication that the envisioned development occurred. More green, the longer we had to wait.

One thing that comes right out, at me anyway, is the earlier works had much, much longer to wait before what they foresaw came into being. The laser visionary works gave much shorter lead times. This tells me something about technology and the willingness of the writers to go out on a limb. Writers today have so much instant information to work with, thanks to the Internet, the 24-hour news cycle … time was, we had to go out and get our information. These days, it gets pushed at us so fast that those basements we used to blog out of in the last decade are being used to hide from the onslaught in this.

More, so much newness is feeding back into the system so fast that it's influencing things a a much more pitched rate than ever before.

See, that's the difference I have with the 'SF as predictor' trope. SF doesn't predict anything. We see things we recognize in society and evolve to meet us. SF has never predicted anything, it's really just given us our number, gauged our character, and the most apt SF writers have taken these traits and played with them as a happy child with Legos does, putting them together into different combinations with situations and then seeing how they react. Are they stable … or do they fall apart?

Since SF so quickly enters the pop culture these days, it goes from entertainment to zeitgeist in record time. We evolve the direction we think it shows us because it's really not telling us anything we don't know about ourselves; we look into SF and see ourselves reflected back. SF only exists in the future because that's the place we're all going anyway.

So, I don't see SF as some sort of oracle; sure, Star Trek 'predicted' things like the iPad and the smart phone, but did it? We've always liked portable, flashy toys, and instantaneous communication and entertainment via personal devices didn't start with Star Trek. It just picked up a well-played ball, dressed it up in chrome and flippy cover, and ran with it with inimitable style. That's not to say that Trek didn't do it smashingly well … it did. I just thing that Trek gets maybe a little too much credit for envisioning our personal technological future. Dick Tracy gave us the 2-way wrist radio, after all.

Rather than predicting anything, SF does a sort of odd dance with the present, whispering into our ear what things might look like, and also asking us to think about them and what they do to us. Of course, we only half listen to that. But it's there, if we pay attention.

Maybe, like the crows we frequently make fun of, we get too obsessed with the bright shinies.

No comments:

Post a Comment