2981.

The sort of thing I troll the intearwebz for, since my adoration of city street grids and the maps thereunto has never waned. involves putting search terms such as "city grid pattern" into teh Google and seeing what interestingness comes up.I have preferences. I adore a square grid that starts at an angle, aligning some local reason-to-be, and then straightens out as the planners adopted a cardinal-north orientation as the city grows. I love the way the central grid is tilted to follow the railroad track, the way it gently bends as the city grew east, west, and south (not much room on the north, with the Snake River and all.

View Larger Map

I like the layout of Canton, Ohio for the same reason, though I seem a bit obsessed with it. Maybe it's because it was the first city outside of the Pacific Northwest that named and gave directional suffixes to its streets in the manner that cities in the PNW tend to do (which was, I realize now, something of a misconception, but still, it seems a particularly Cascadian thing to do).

While we will see what we want to see, pareidolia being what it is, patterns do crop up. Cities are planned around human wants and needs, or at least what they're perceived to be, and being the sorts of artists that they are, city designers like to lay symbols in, or at least seem to. Washington DC, being founded and planned by men who were deeply involved in so-called 'secret societies' such as Masonry (it always seemed funny to me that secret societies should have easily located temples and used resources on the shelves at Powell's, but maybe there's a roguish meaning to the word I've not considered) has its legends of Masonic symbols baked into the city design, which are both advocated for and dismissed.

But what if there really was a city with a Masonic design in it? It's not so odd as one might think. We humans, whether we're Masons or not, love us our symbols and designs … a whole industry has grown up on creating them.

At the blog Masonic Traveler, the eponymous author makes a case, convincing, if brief, for just such a place, but no place so big or fashionable as the capital city … it's Sandusky, Ohio:

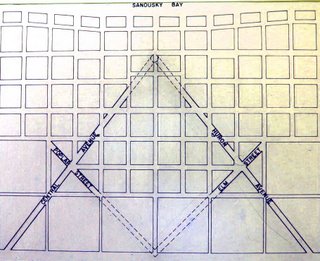

I found the city of Sandusky, Ohio, where the original grid planner, a Master Mason named Hector Kilbourne, built the biggest symbol of freemasonry right into the cities layout. Kilbourne also happened to be the first Worshipful Master of the Sandusky Masonic Lodge.The original layout of the city's plan certainly seems to bear him out here (included from that blog for purposes of illustration):

Compare with that most culturally-recognizable of Masonic emblems, the compass-and-square logo:

It would seem as good an explanation as any. I personally don't see any problem with baking a symbol like that into the design of a town - it makes an interesting frame to create a community around, what with its diagonal streets, triangular blocks, and interesting intersections forming possibilities for public squares and quirky parks.

Of course it depends on the symbol. If I saw a town based on a Nazi-esque approach to the swastika, I'd likely recommend quick and thorough urban renewal, were my opinion to be asked.

On to a another interesting find, ever notice how, sometimes, something sticks out and seduces you into wondering why. Josh Jackson, the author of a blog post at LOST magazine, tells us about his personal, human experience with such a thing:

Last fall, I was walking through Prospect Heights, Brooklyn, when a residence caught my eye. The building was a fairly standard one — a classic three-story brownstone built, in this case, from brick. Rather, what caught my eye was its position: it was rotated about 60 degrees from the rest of the street grid. Buildings don't build themselves, and whoever built this one located it the way they did for a reason. Especially in brownstone Brooklyn, where row houses are the dominant architectural feature, buildings usually face the street.In this case, either someone decided to build it differently or the street it once faced no longer existed.The buildings he mentioned are near the intersection of Prospect Place and Underhill Avenue, in Brooklyn, NY. The buildings he mentioned do rather stick out like the proverbial sore thumb in a view from the air (courtesy Google Maps)…

Just as interesting to me is the way the wall, and one would imagine through inference, property line, of the building to the immediate right (east) and the lot east of that, coincide exactly with the canted buildings along Prospect Place. That diagonal street at the right-hand edge of the picture is Brooklyn's Washington Avenue, and we do immediately notice that the angle of the buildings align more with this street than they do the streets they actually abut.

Why? I mean, we can probably deduce there was some survey before that somehow governed the different buildings, but where the real interest comes is in exactly what those reasons, now obscured by centuries of development, must have been.

In the article linked in the pull quote above, Josh goes on a quest almost Holmsian in terms of deduction and certainly compelling in terms of interest.

It might be better termed Finding Flatbush Turnpike. But read it anyway. And marvel upon the things one finds when they try to figure out the exception to the rule.

In case you don't want to scroll back up, here's the links:

The Masonic Traveler's article on Sandusky OH is at http://masonictraveler.blogspot.com/2006/10/coincidences-and-tangents-sandusky.html.

Josh Jackson's LOST Magazine article is at: http://www.lostmag.com/issue14/prospect.php.

Happy hunting.

No comments:

Post a Comment